Local Legends: The art of war

"Barrows attended Miami University in 1853 and became a member of the Erodelphian Society, a student literary society on campus. However, Barrows did not complete his studies and left the university in 1854."

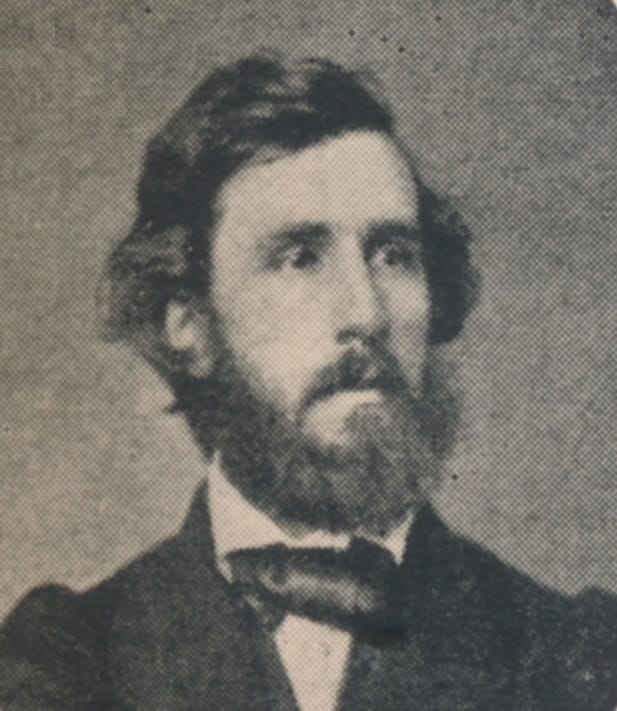

Artist, poet, soldier and war correspondent Charles Cornelius Barrows lived a short life devoted to his craft and his faith.

Barrows, whose name was also commonly misprinted as “Burrows,” was born in Oxford in 1833, though his exact birthdate is unknown. His parents, Charles, a carpenter and native of Vermont, and Mary (Anderson) Barrows, were Oxford pioneers. They were married in the village in 1819.

The family lost one child, James Barrows, three years prior to Barrows’ birth. By the time Barrows reached adulthood, his father had also passed, leaving only himself and his mother in the household.

Barrows attended Miami University in 1853 and became a member of the Erodelphian Society, a student literary society on campus. However, Barrows did not complete his studies and left the university in 1854.

From an early age, Barrows developed an interest in painting, and his artwork became his obsession. He especially loved landscape painting with his works showing his awe and appreciation for nature.

Although extremely talented at his art, Barrows was purportedly self-taught and painted in a variety of different styles. He likely never received any extensive formal training, though a reference does survive to Barrows receiving some limited instruction from a Western Female Seminary professor.

Raised in a devout Presbyterian household, Barrows held his faith close and seemed to experience God through nature. In a letter to his mother, he wrote, “I went along up the beautiful banks of the river where I could be alone and meditate on God’s word and works. I read the Thirty-first Psalm and poured out my soul to my Creator in fervent prayer.” Barrows wrote of his Bible, “It is my companion, my support in doubt, my comfort, my teacher, and at all times my exceeding great joy.”

The young artist became close friends with George Washington Keely and in 1860, Keely, along with Robert Hamilton Bishop Jr. and Lazarus N. Bonham, paid for Barrows to travel to the White Mountains in New Hampshire. Barrows produced a landscape painting, “The Franconian Mountains,” during the visit.

One day while walking through a field with Keely, Barrows pointed out a large boulder and remarked that it would make a perfect headstone, stating that he “would want no better monument when he died.”

Barrows’ landscapes, such as “Lake George,” “Mote Mountain” and “Mount Washington,” became highly sought after by local collectors, and many were held onto by families for generations. Some of Barrow’s poetry, another of his hobbies, made its way into local publications.

On August 8, 1862, Barrows enlisted in Company C of the 93rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, under the command of future Governor of Ohio Colonel Charles Anderson. The unit mustered in at Camp Dayton before being dispatched to Kentucky, where it was held in reserve during the Battle of Perryville, on October 8, 1862.

Barrows received his baptism by fire at the Battle of Stone’s River on the last day of 1862. In the second hour of the fighting, the 93rd OVI and the rest of its brigade were routed off the field in chaos by an onslaught of Confederate Arkansans from Cleburne’s Division. The brutality of combat starkly contrasted with Barrow’s peaceful and religious nature.

The 93rd OVI remained on duty in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in the months following the battle. During that time, Barrows’ skill was brought to the attention of Major General William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Cumberland, who assigned Barrows the task of sketching the area.

Some of these sketches were published in the April 4, 1863, issue of Harper’s Weekly, the most widely read political magazine of the era for which Barrows had also been a contributing correspondent.

Eleven days later, Barrows was dead. He had contracted typhoid fever and succumbed to the disease on April 15, 1863, at the age of only 30 years old.

Arranged by Keely, a team of eight horses were required to drag the boulder Barrows had pointed out to his grave at the old village cemetery. His remains were later disinterred and relocated to Oxford Cemetery, as was his unusual headstone.

The Village of Oxford greatly lamented his demise. His obituary stated, “Charles Barrows was one of the few who, ignoring the gilded baubles of the world, devoted life and talent to God and art...may we profit by example and live while opportunity offers as pure and useful lives as did our departed friend.”

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects.