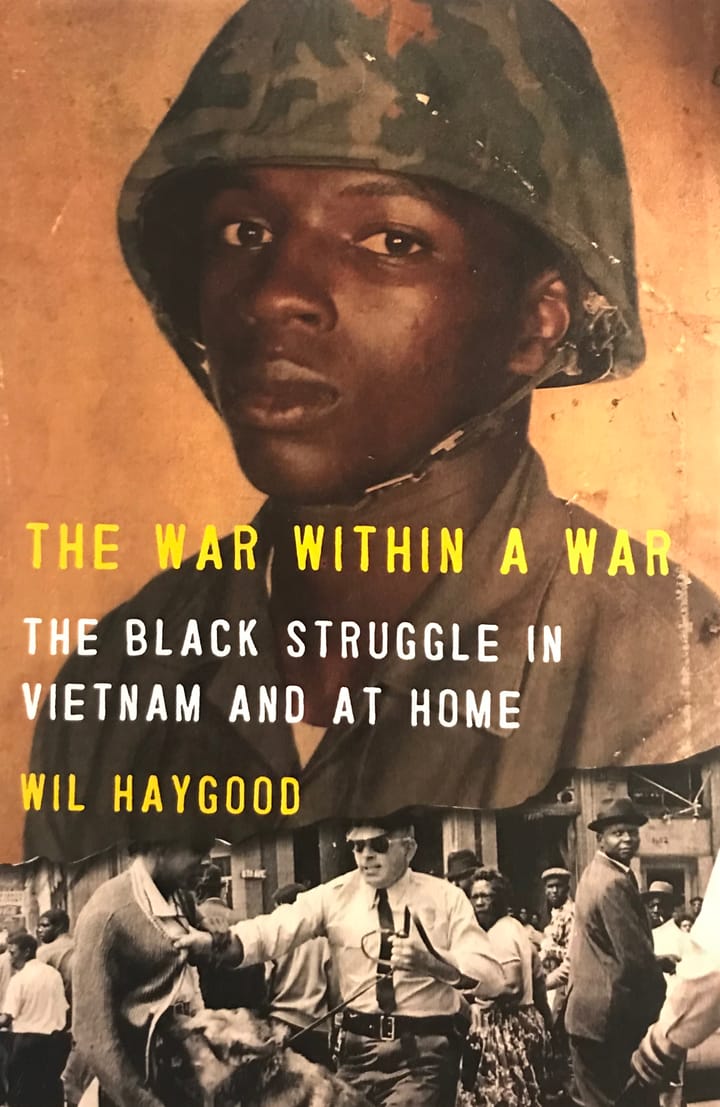

Local Legends: The civilian hero

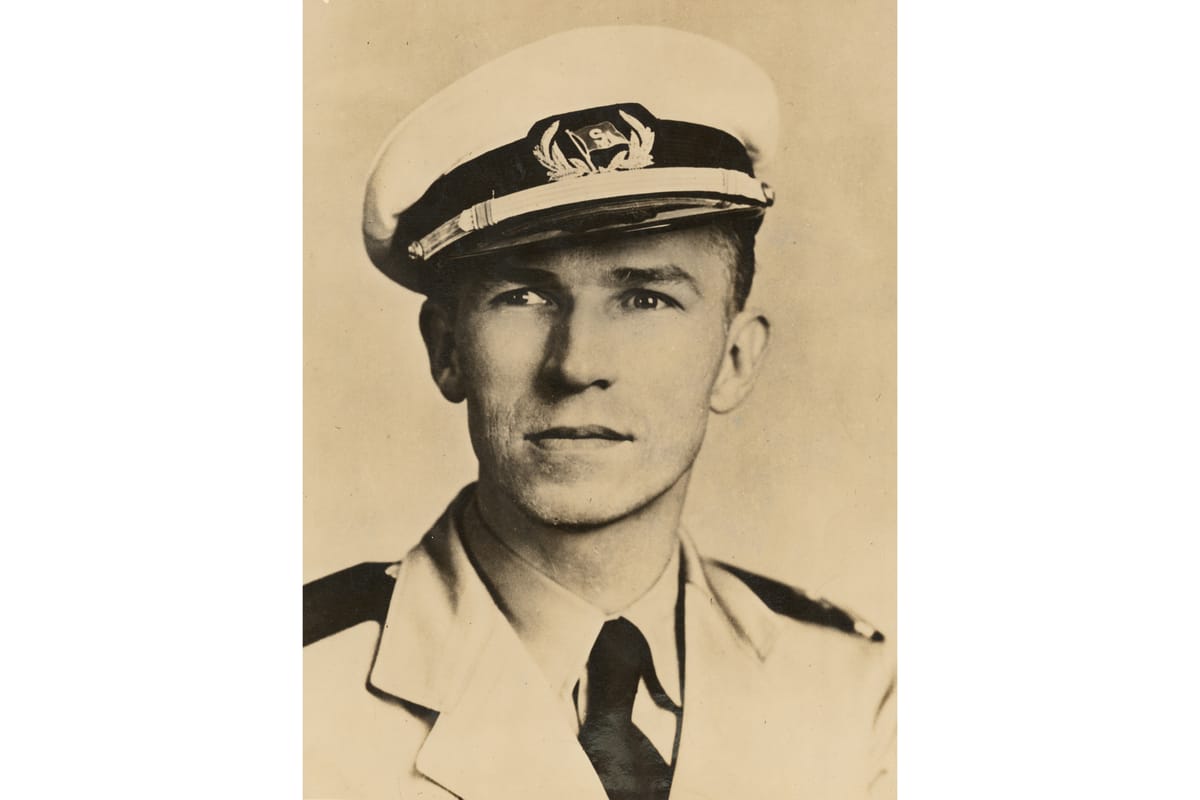

Philip Carter Shera, born and raised in Oxford, wasn't a member of the U.S. Navy, but he still earned high honors for service during World War II.

With the coming Memorial Day is a special remembrance of the 80th year since the end of World War II and the service members of the U.S. military who sacrificed their lives during the war. However, members of the military weren’t alone in sacrificing themselves in the pursuit of victory.

Philip Carter Shera was born Oct. 28, 1904 in Oxford and grew up in the village. His father, George M. Shera, was a banker and insurance agent and his mother, Alice (Carter) Shera, was an artist and homemaker.

Shera’s first experience with service came in the summer of 1921 when he attended an ROTC camp for high school students. He had been gifted a Doble steam car for Christmas in 1917 and used it to drive himself and Colonel John H. DeArmond, commander of Hamilton High School’s ROTC, to the camp.

Finishing out his final year at Oxford Public School the following year, Shera was chosen to speak at his class commencement and delivered his speech, “Our Material and Moral Progress.” He attended Miami University the following Fall but dropped out in 1924 during or after his sophomore year.

He married Sera (Matthews) Shera on March 7, 1925 in Indianapolis. The Sheras soon moved to Columbus, Ohio where their son, Philip Carter Shera, Jr., called “Tippy” by the family, was born on Aug. 15, 1926.

Shera lost his mother on April 19, 1936 following an operation. She died in Harlan, Kentucky, where she had been teaching art at the Pine Mountain Settlement School.

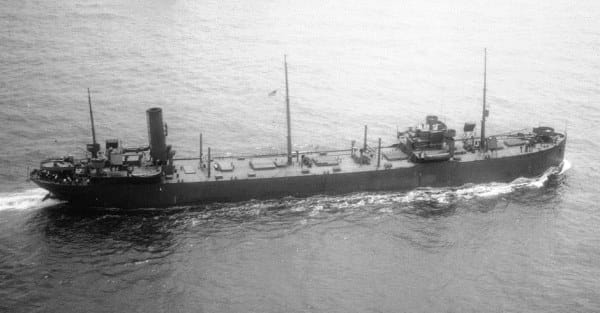

Shera spent about a decade working in Columbus, first for the Pure Oil Company and then as a statistician for the Ohio Department of Aid for the Aged. In 1936, he got a new job as a merchant mariner with the Socony-Vacuum Oil Co. Inc. of New York. He worked his way up to the position of third assistant engineer aboard the company-owned steam oil tanker S.S. Java Arrow.

With the start of World War II, shipping became essential, leading to the creation of the War Shipping Administration by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in early 1942. The temporary war agency was created “for acquiring control over and operating all American merchant vessels other than those assigned to the Army and Navy.”

The 36-year-old Shera now found himself in the U.S. Merchant Marine transporting oil for military use across waters infested with Kriegsmarine U-Boats hellbent on destroying every Allied vessel they came in contact with.

The Java Arrow steamed away from port, about eight miles off the coast of Vero Beach, Florida on May 5, 1942. Having fallen behind the rest of its convoy, the vessel ceased zigzagging, a standardized anti-torpedo tactic, and steamed at full speed trying to catch up.

Corvette Captain Peter-Erich Cremer, commander of U-333, sighted Java Arrow through his periscope. U-333 was on the 36th day of its war patrol stalking the Atlantic Coast when it came upon the oiler.

Cremer fired a single torpedo, which swam through the waves and detonated against the hull of the Java Arrow, a devastating blow that crippled the ship instantly. Working in the engine room, Shera felt the impact of the explosion and without hesitation ordered the other engine room crew members topside.

Recognizing that his ship was moving too fast to safely launch life boats, Shera stayed behind in the engine room, alone, and throttled down the ship’s engines. He then began shutting off the engines entirely to prevent their boilers from exploding.

As crew members began loading into lifeboats to abandon ship, Cremer fired a second torpedo toward the Java Arrow, sealing its fate and that of Shera.

A group of crewmen delayed their own salvation to try to reach Shera, whose screams could be heard from below decks. They were forced to abandon their rescue operation by live steam blasting through destroyed pipes.

As U-333 slipped away with its kill, U.S. Coast Guard vessels appeared at the scene and began rescuing survivors. Because of Shera’s sacrifice, 44 souls aboard the ship were saved, all but one other crewman who was killed in one of the explosions.

Sera was notified of her husband’s death on May 7, five days before news of the attack became public. Despite taking two critical hits, Java Arrow remained afloat and was towed back to Norfolk, Virginia for repairs. On July 20, crews at Norfolk working in the flooded engine room discovered Shera’s remains, which were cremated and later interred in Oxford Cemetery.

In February 1943, Sera accepted the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal which had posthumously been awarded to her late husband. The citation for the medal, which was the highest award of the Merchant Marine and equivalent to the Medal of Honor for the military, concluded, “His extraordinary courage and fidelity to trust will be an enduring inspiration to seamen of the United States Merchant Marine everywhere.”

Shera was also awarded the Mariner’s Medal, the Merchant Marine’s equivalent of the Purple Heart. In December 1943, Sera was invited to christen the new Liberty Ship Philip C. Shera (2545), named in Shera’s honor.

Philip C. Shera Jr. received an appointment to the Merchant Marine Academy in 1943. A year later, he himself exhibited heroism when he and another mariner pulled the victim of a maritime collision to safety.

Serving in Okinawa in November 1945, Shera’s ship came up alongside the Coast Guard vessel Karry Patch. He recognized it as the very same vessel upon which his father had died, which had been repaired, renamed and put back in service.

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects.