Local Legends: We Will Be There

"Although historical segregation was mainly associated with the American South, it also existed in Ohio, and elsewhere in the North, for many years beginning with the passage of a state law in 1848."

Perry and Sarah “Sallie” (Dickerson) Gibson tenaciously saw to it that their children were educated in spite of seemingly insurmountable and, at times, violent opposition.

Perry Gibson was born, presumably into slavery, in 1839 in Gallatin County, Kentucky and was the son of Lewis and Emily (Steele) Gibson. From later records, it is known that he had at least five younger siblings, including two brothers, Richard and Cupid Gibson, who later lived in Preble County.

Around 1860, Gibson married Sallie, the daughter of William Dickerson, who gave birth to their first three children before leaving Kentucky for Oxford just after the Civil War. Together they eventually raised a total of ten children, James, Jenny, Mary, Fannie, Simon, Charles, Emery, Morris, Daisy and Ben. Both Perry and Sara worked to support their family, Perry as a laborer and Sallie as a washerwoman.

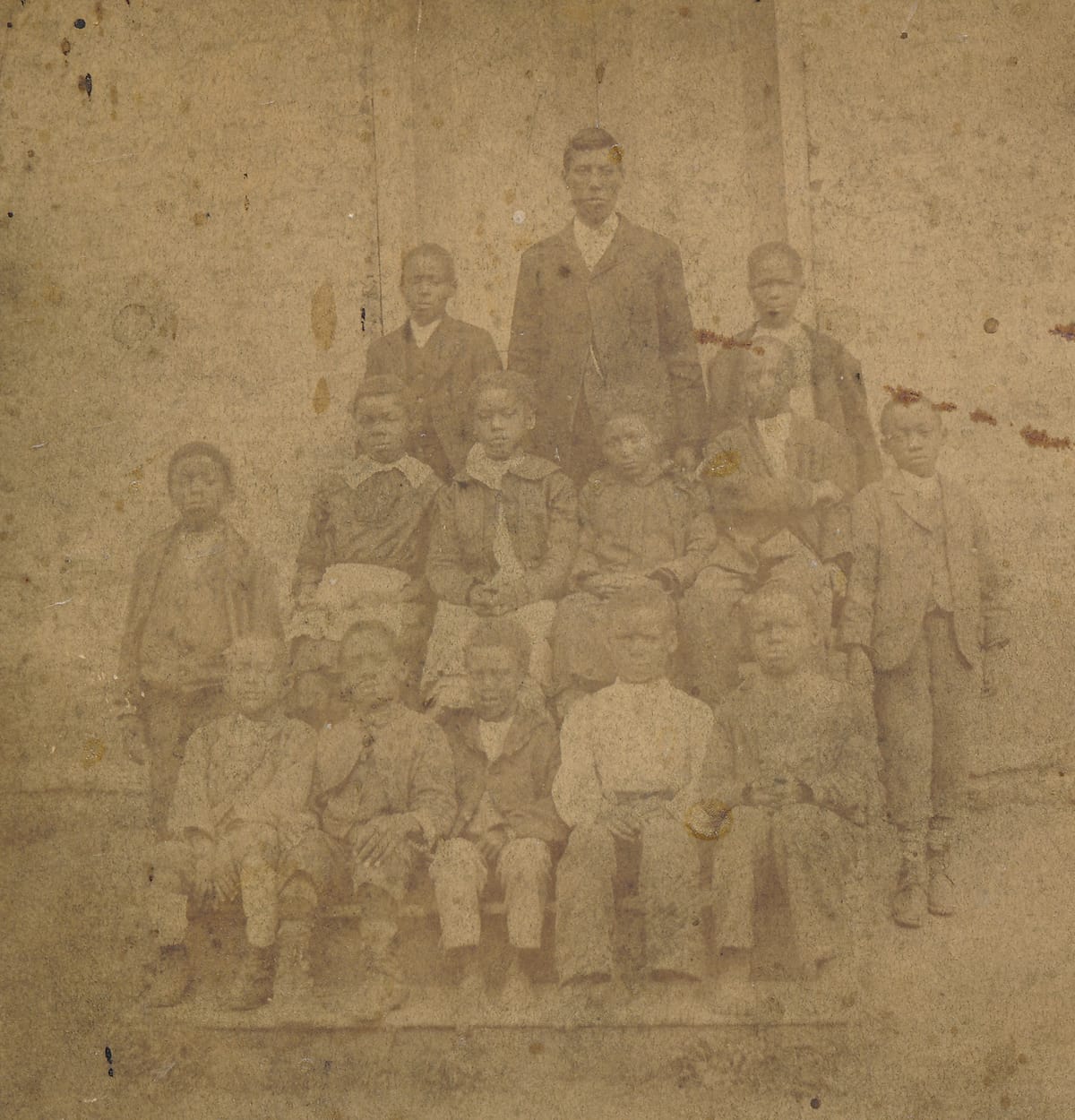

While neither Perry nor Sallie could read or write, the importance of education was not lost on them and all of their children were attending school by the time the family was recorded in the 1870 census. However, because they were Black, their children were relegated to attending Oxford’s segregated North School under longtime teacher Lawrence “Pap” Grennan.

Although historical segregation was mainly associated with the American South, it also existed in Ohio, and elsewhere in the North, for many years beginning with the passage of a state law in 1848. This law served as the basis for the operation of the North School, which was described in the “Centennial History of Butler County” as “twenty-five years behind the times” and “actually unsafe,” while the village’s white children attended the newer South School.

As Oxford grew, overcrowding at both schools became a major issue and a new school building was planned to be built. Simultaneous to the construction of the new school, the state law establishing separate schools for Black children across the state was repealed. The repeal took effect in February 1887 and the new school was completed and dedicated in April 1887.

With the coming new school year, Oxford’s Black families desired to send their children to the new village school, which would have integrated the school. This faced widespread opposition among Oxford’s white citizens, who organized two “indignation meetings.”

Oxford’s school board, serving 1887-1889, was composed of Stephen D. Cone, Tom Law, Dr. J.B. Porter and W.A. Logue with William H. Stewart as superintendent. As the only one among them in favor of integration, Cone refused to join them in attending the first indignation meeting, but despite "hisses, groans and cries of “throw him out of the windows”” did attend the second meeting where spoke in favor of complying with state law.

In the fall, the Black children from the village were permitted to attend the first two weeks of school in the new building before being barred from returning by the school board. When a group of 43 Black children attempted to legally return to school anyway, they were chased away by a mob of angry white citizens. Some reports claimed that the town marshal even used a carriage whip to scare them away.

Unrelenting in their pursuit of a quality education for their children, the Gibsons refused to back down. In December 1887, Perry Gibson traveled to Hamilton by buggy where he filed suit in the Butler County Court of Common Pleas to allow his children to attend school, engaging the Hamilton law firm Morey, Andrews, & Morey for representation.

The Oxford School Board, represented by Hamilton attorneys Thomas Millikin, Alexander Hume and Palmer Smith, argued that because they retained the right to assign children to school buildings that would best promote their education, they had the right to assign all of their Black students to a separate school. Judge C.J. Smith ruled that Gibson’s children could not be denied access to the new school building based solely on their race.

While Gibson was victorious, there was immediate backlash in Oxford. When Gibson sent his children to school, superintendent Stewart refused to admit them until telegraphing the district’s lawyers and who responded by saying that the children should be refused admission until the court ruling was on the record.

A large portion of Oxford’s Black population, desiring to send their children to the new school as well, had worked to help finance the case, some of whom even mortgaged their homes. In response to the ruling, white citizens of Oxford threatened to stage what a newspaper called a “boycott,” refusing to hire Black workers.

When asked about the potential boycott by a reporter, Perry dismissed it as “silly talk,” pointing out the interdependence of the white and Black communities in Oxford. When questioned about pursuing the case further, Perry responded, “If they carry it to the Supreme Court, we will be there also, to fight for our rights…we recognize our rights and are going to have them.”

The Oxford school board did appeal the lower court’s decision to the Ohio Supreme Court, who, in 1888, also sided with Gibson. In doing so, the Supreme Court not only affirmed the integration of Oxford’s public schools, but also affirmed the integration of all of Ohio’s schools seven decades before the landmark U.S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board decision.

Perry Gibson lived the remainder of his life in Oxford, dying on April 22, 1915 at the age of 75. Sallie passed away a few months later on June 8 at the age of 73. Both are buried at Woodside Cemetery in unmarked graves.

A year before the court case, on April 15, 1886, the Gibsons’ youngest son Ben Gibson was born. It was only because of his father’s perseverance that he attended Oxford’s public school throughout his childhood. In January of 1946, Ben Gibson was elected to Oxford City Council, a position he would occupy for the remainder of life, serving five consecutive terms until his death in 1954 at the age of 68.

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects. He also serves as a board member for Historic Hamilton Inc. and the Butler County Historical Society.