Media Matters: 'Biased,' 'Boring' and 'Bad'

These words – biased, boring, and bad – describe U.S. teenagers’ “perceptions of news media and journalism,” according to the latest News Literacy Project.

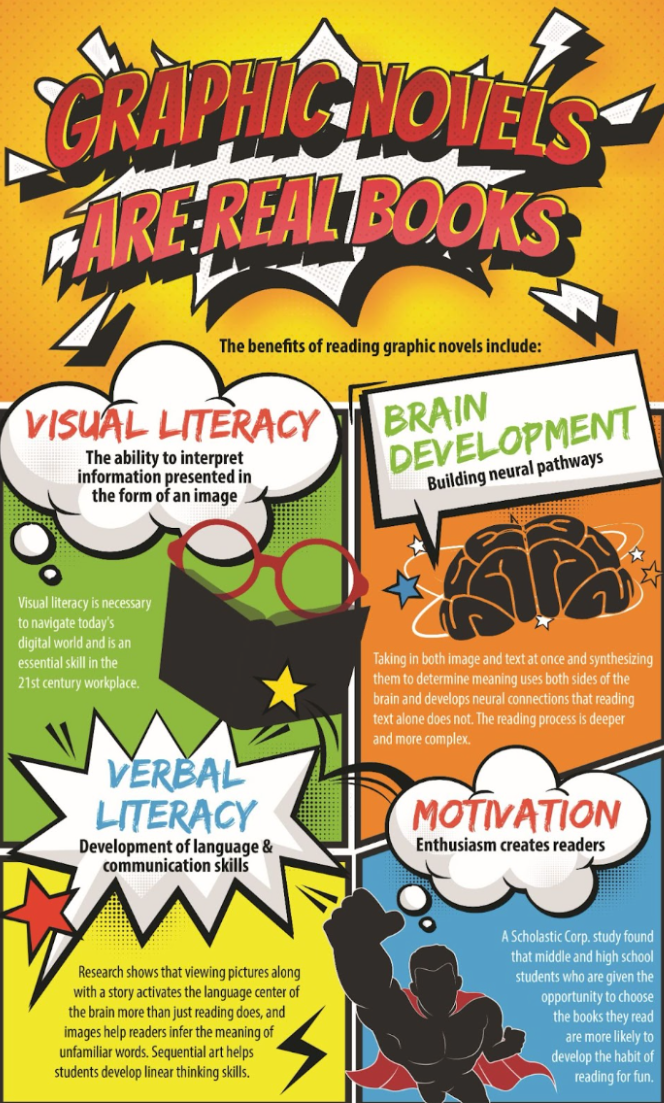

You would think that since two of our most beloved superheroes – Superman and Spider-Man – had side jobs in journalism, U.S. teens would have a better attitude toward the profession.

Not so. Here are four key findings from the project, a follow-up to its 2024 report:

- Almost half of teens (45%) said journalists do more to harm democracy than to protect it.

- Only a little over half of teens (56%) believed that journalists and news organizations journalism take standards such as accuracy and fairness seriously in their work.

- The majority of teens (80%) said that journalists fail to produce information that is more impartial than other content creators online.

- Nearly 7 in 10 teens (69%) thought that news organizations intentionally add bias to coverage to advance a specific perspective.

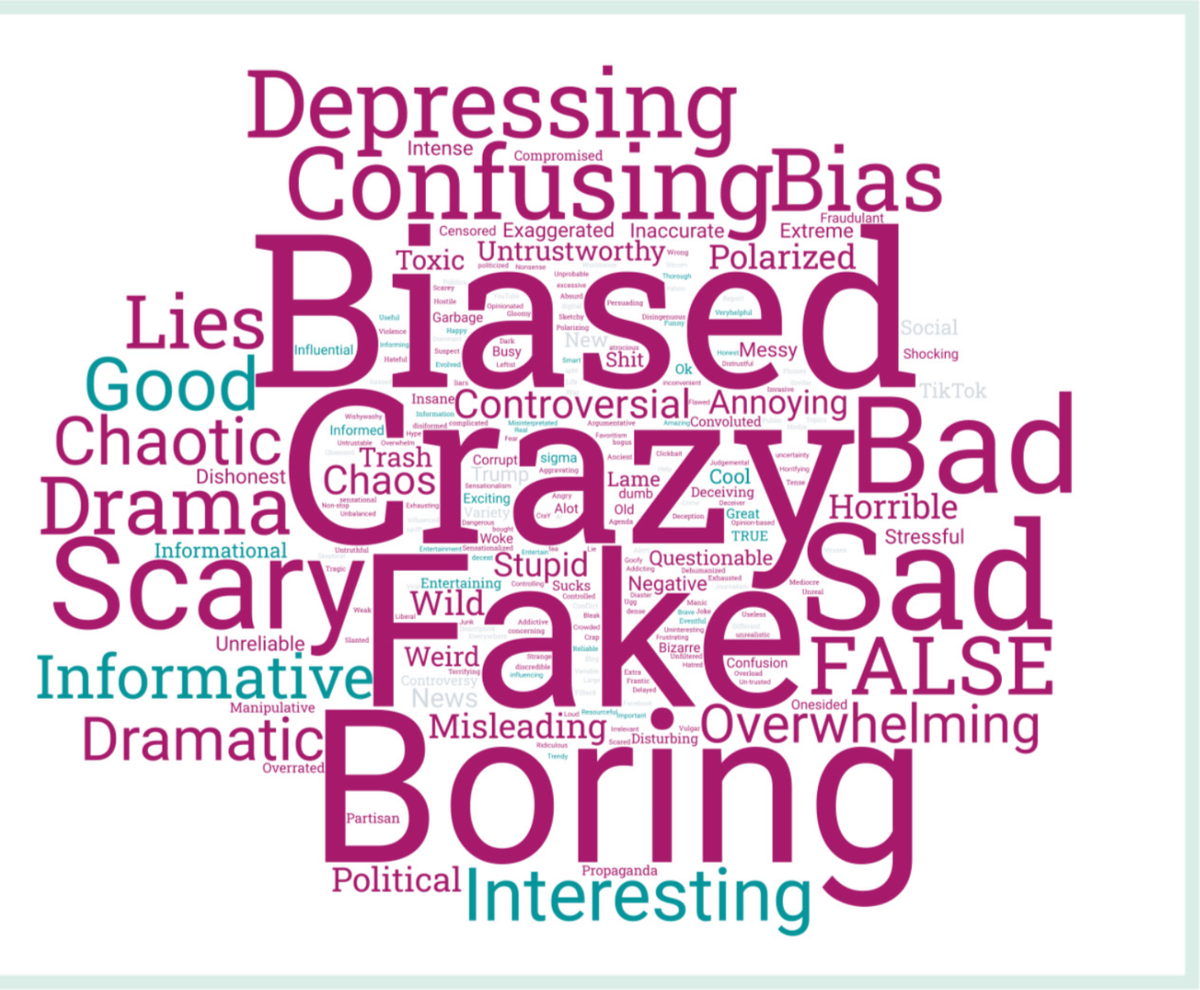

The project also notes that the majority of the study’s 750 teens (84%) used negative words to describe “news media.” The top word choices: fake, crazy, boring, biased, scary, bad and sad.

While this report is certainly troubling news for Baby Boomers who grew up on newspapers, it’s not hard to understand. A study back in 2018 by the American Psychological Association reported that only 2% of U.S. teens read newspapers on a daily basis.

I suspect it’s even less today.

One of the problems going on here is the sloppy use of language. The term “media” refers to all sorts of industries, including books, magazines, radio, TV, movies, music and journalism – in its print, television and digital forms. So to say that “the media are biased” or “the media are boring” – now that’s truly sad. Which media are you talking about?

Journalism is reporting and storytelling. It is hard work by trained reporters. It’s what most of us rely on to learn what’s happening locally, nationally and globally. To tell the best stories, reporters talk to a lot of people, research multiple topics, study documents and then engage readers, listeners and viewers in a narrative. Reporters try to be fair, which is not easy. Journalism is not a science. It’s also not about telling “both sides of a story,” because there are usually more than two. It’s not just about what the left and the right think. There’s also a wide middle ground, where most of us reside. Good reporters cover that middle ground too.

Given that only about 30% of us have “a great deal” or “fair amount of trust and confidence” in the news media, it’s not rocket science that teens diss journalism. The distrust is modeled at home. It’s the same place where most teens get their politics – from their parents. It’s the same place where they no longer see newspapers.

Journalism itself shares some blame. Journalists do a lousy job covering journalism. The best example is the crisis in local news and the emergence of news deserts, with nearly 50% of the U.S.’s 3144 counties having little or no access to local news. This drives many of us to get information from cable hosts, talk radio and social media. The national news media are not covering this as a national crisis. As I’ve reported before, we’ve gone from 40 reporters per 100,000 residents three decades ago to just 8 today.

The News Literacy Project offers a grim outlook: “If the majority of teens believe that trustworthy, standards-based news is either rare or nonexistent in today’s information environment, this belief not only threatens the viability of the press as an important watchdog and guardian of democracy but it also leaves those teens highly vulnerable to manipulation and influence by political propagandists, trolls, conspiracy theorists and ideological extremists. This susceptibility to low-quality information sources disempowers teens personally and in their community, diminishing their ability to make well-informed decisions about their own lives on topics such as their health, and making it harder to participate effectively in our shared civic life.”

After revealing the scary and sad stats, the report offers recommendations, including learning the distinction between “the media” and “high-quality journalism.” The report also advocates teaching the difference between opinion-driven “news” and “standards-based” journalism. In “The Elements of Journalism,” Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel call the first type “the journalism of assertion,” driven by cable and radio pundits and social media influencers. They contrast this with “the journalism of verification” or standards-based journalism: disciplined reporting that cites reliable sources and actual evidence.

I like to think of reporting and writing as superpowers. After all, most people don’t like interviewing strangers nor do they like to write. I taught a lot of smart business students in my career who knew a lot about finance but feared writing. In these times, taking a journalism class should be mandated for all high school and college students. We need schools and states to push news literacy in high school curriculums. We need universities like Miami to take a leadership role. But, most of all, we need young people as reporters, monitoring civic life and telling a community’s stories.

Richard Campbell (campber@miamioh.edu) is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami University. He is the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.