Media Matters: To ban or not to ban

Challenges to books in public school libraries have risen sharply in the past five years. Columnist Richard Campbell writes that the Trump administration's efforts to clamp down on materials that promote diversity have put librarians at the center of a political fight.

When I found out that Miami University alumnus Wil Haygood’s book on Black film history, “Colorization,” was among 381 titles banned from the U.S. Naval Academy Library by the Trump administration, I had two thoughts. One, “Wow, this is going to be good for Wil’s book sales!” And two, “Why wouldn't naval cadets be tough enough to handle a book about movie history … aren’t they being trained to fight in wars?”

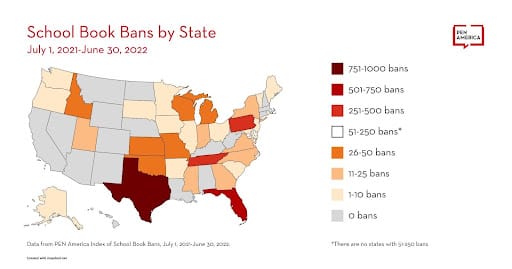

Since 2020, there’s been an alarming rise in the number of books challenged in the U.S. for their right to exist in libraries, according to American Library Association (ALA). In 2020, less than 300 book titles were challenged, but that figure ballooned to nearly 4,000 in 2021 and over 9.000 in 2023.

Over the years, such challenges typically came from parents or school boards worried about the effects of a book’s sexual content on children — although between 2000-2009, the Harry Potter series faced the most challenges, apparently for encouraging witchery.

Judy Blume, who wrote books for children and young adults, often saw her books targeted or banned. The author of “Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret” (1970) and “Forever” (1975) once offered this advice: “Let children read whatever they want and then talk about it with them. If parents and kids can talk together, we won’t have as much censorship because we won’t have as much fear.”

The last Supreme Court case to address book banning, more than 40 years ago, was Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982). The Court’s fuzzy ruling stated that “local school boards have broad discretion in the management of school affairs.” But then the Court wrote that such discretion “must be exercised in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.”

More recently, many of these challenges have been political, as the ban on “Colorization” suggests. The recent surge is part of the newest iteration of the “culture wars” over the rise of diversity, equality and inclusion programs, DEI for short, that have developed in schools and colleges over the last two decades.

On one side of the cultural spectrum are efforts to acknowledge the histories of minority populations, long ignored or discriminated against. On the other side are those worried that books promoting DEI efforts are getting too much attention, upsetting old norms and traditional values.

“The record number of book challenges we’re reporting today are not the result of parents filing authentic requests for reconsideration,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom, discussing the organization's data. “Overwhelmingly, we’re seeing groups and individuals at library board meetings demand the removal of long lists of books obtained from organized censorship groups who share these lists on social media.”

As states go, Ohio stands out as less censorial than many:

In 2023, though, ALA reported 40 attempts to remove 235 titles from school and public libraries in Ohio. In Butler County, the Lane Libraries report only three challenges since 2020.

Amanda Toth, Lane’s Adult Collection Development Librarian, told me their process is based on finding appropriate materials for individual families, not on censoring materials for everyone.

“We are here to support the needs of all different individuals and families,” Toth said. “We don't decide what is right because every family has different needs. We take challenges seriously and make sure to review the item as a whole in its value to the community.”

Before 2020, according to Education Week, “Book challenges involved a parent’s objection to a single book, instead of an organized movement.” But after 2020, PEN America, a free speech advocacy organization, identified more than 50 different groups that have emerged, some with multiple chapters, targeting long book lists at both the local and state level.

According to reporting by the New York Times, a team of political appointees waded through such a list to decide what to remove from the Naval Academy library, using keyword searches to flag any book title that smacked of DEI. Those terms apparently included words like “race” and “black.” It’s not known whether the appointees read each book. Maya Angelou’s celebrated “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” (1969) got banned, so given a title that lacked DEI trigger words, someone must have skimmed it. The Times also reported that Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” survives in the library.

Former President Barack Obama has offered some insight on this, with a nod to librarians: “Today, some of the books that shaped my life and the lives of so many others — are being challenged by people who disagree with certain ideas or perspectives. And librarians are on the front lines, fighting every day to make the widest possible range of viewpoints, opinions, and ideas available to everyone.”

Author Kurt Vonnegut once offered a compromise of sorts — one that I can get behind: “All these people talk so eloquently about getting back to good old-fashioned values. Well, as an old poop I can remember back to when we had those old-fashioned values, and I say let’s get back to the good old-fashioned First Amendment of the good old-fashioned Constitution of the United States — and to hell with the censors! Give me knowledge or give me death!”