Media Matters: Inventing television

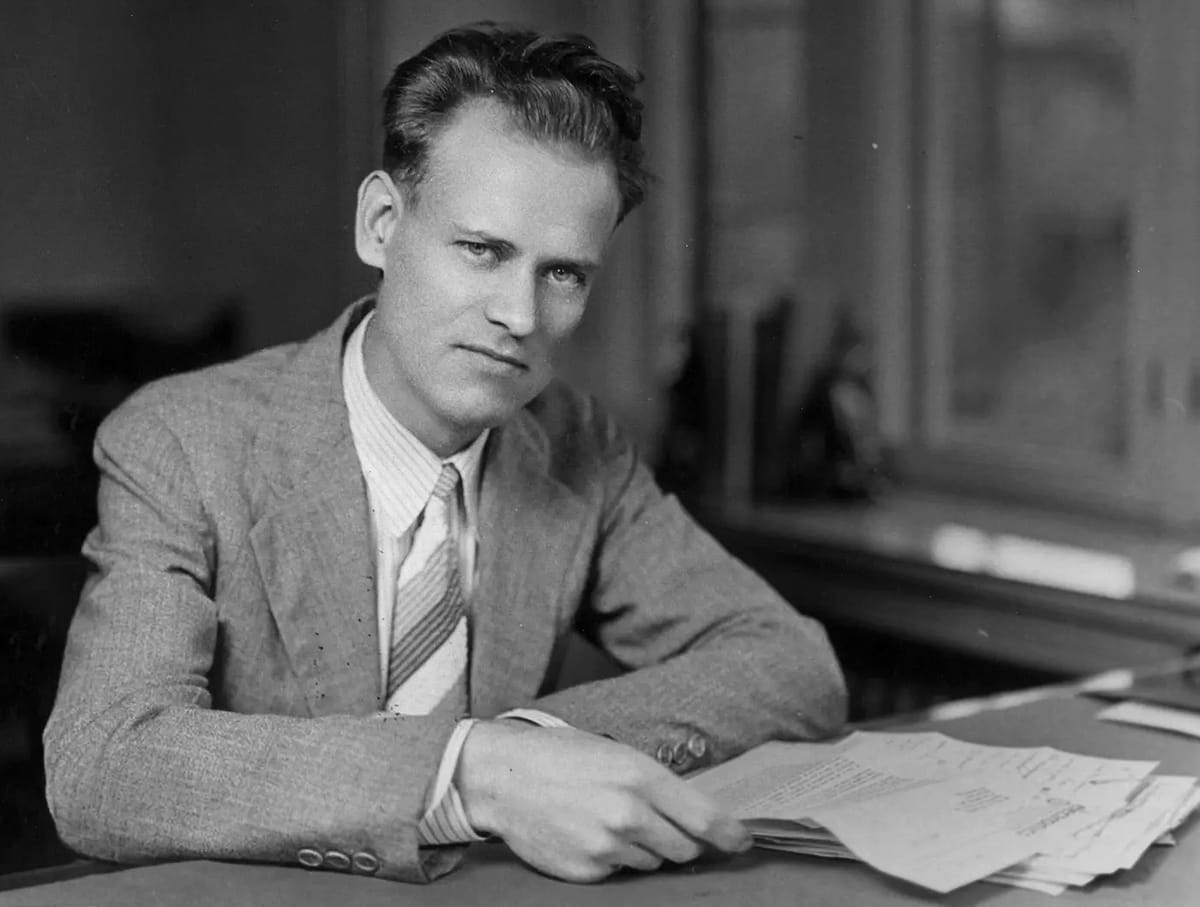

Philo T. Farnsworth – a character in a Dickens novel? Not even close.

He is possibly the most notable American inventor you have never heard of. He had his own statue in the U.S. Capitol (since moved to Utah) acknowledging him as “The Father of Television.”

That’s not completely true. There’s a long line of inventors working across multiple countries who helped father TV. The Scottish inventor John Baird is credited with producing the first TV image in 1925. He used a whirling scanning device that relied on a mechanical motor. The Russian scientist, Vladimir Zworykin, who worked for Westinghouse and later the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), also contributed.

Writing for the MIT Technology Review, Evan Schwartz – who wrote a recent biography of Farnsworth, “The Last Lone Inventor” – recounted Farnsworth’s early life as a child prodigy, a high school student studying at Brigham Young on the side:

“Farnsworth dreamed up his own idea for electronic – rather than mechanical – television while driving a horse-drawn harrow at the family’s new farm in Idaho. As he plowed a potato field in straight, parallel lines, he saw television in the furrows. He envisioned a system that would break an image into horizontal lines and reassemble those lines into a picture at the other end. Only electrons could capture, transmit and reproduce a clear moving figure. This eureka experience happened at the age of 14.”

“I have abandoned the old idea of a whirling disk with its motors and other contraptions,” Farnsworth told the New York Times in 1930. “A simple beam of light now does the trick. The entire receiver of images, including the tube and its power unit, can be housed in a box slightly larger than a foot in dimension.”

Farnsworth projected the first fully electronic TV image in 1927 – a single straight line. He used a cathode ray tube (similar to the glass tubes that powered radios) to scan lines across a screen. His invention became the backbone of analog TV sets – with their weighty picture tubes – until digital flat-screen TVs arrived in 1998 (initially, a 42-inch model that cost $15,000).

Meanwhile, over at RCA, Zworykin was having trouble converting to an electronic system and needed Farnsworth’s patents. RCA President David Sarnoff and his lawyers sued Farnsworth, claiming he violated Zworykin’s patents. The drawn-out legal battles took a toll on Farnsworth throughout the late 1920s and 1930s. Farnsworth ultimately won in court, successfully defending his inventions. So RCA bought the rights to those patents for $1 million, eventually helping drive Farnsworth’s TV company out of business. He later suffered from depression and alcoholism and died in 1971, at age 64.

Highlighting his invisibility, a 1966 Sarnoff biography chapter titled “The Struggle for Television” never mentions Philo Farnsworth, even though the inventor held over 300 patents worldwide. A further irony: Farnsworth’s 1957 appearance on CBS’s long-running quiz show “I’ve Got Secret.” No one recognized him, nor did they guess his profession. For stumping the four panelists, he won $80 and a carton of Winstons.

Many inventors have credited or discredited God in their work. Thomas Edison was a nonbeliever. Samuel Morse famously transmitted, “What hath God wrought,” in the first official telegraph message sent in the US in 1848. Farnsworth gave God more credit: “Television is a gift of God, and God will hold those who utilize his divine instrument accountable to him.”

While I am not sure about God’s position on television, the cultural critic Neil Postman had a lot to say about it in his 1987 book, “Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business,” which addressed the seismic shift from a print-based culture to an image-saturated culture in the 20th century.

“It is a mistake to suppose that any technological innovation [like TV … or the Internet] has a one-sided effect,” Postman wrote. “Every technology is both a burden and a blessing; not either-or, but this-and-that.”

Following the burden/blessing metaphors, we could argue that television has given us at least three presidents: John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump. Kennedy benefited from looking more relaxed and tanned than Richard Nixon in the first presidential TV debate in 1960. Reagan, already a movie star, switched to TV when it arrived, appearing in early anthology dramas and hosting “General Electric Theater” and “Death Valley Days.”

David Sarnoff’s old network, NBC, helped rehabilitate Trump, who was already a minor celebrity. Trump hosted “The Apprentice” for more than 10 years – with “You’re fired!” as his mantra. The show ranked as high as No. 7 in the ratings in the 2003-04 season, averaging 20 million viewers and cultivating his image as a successful businessman, despite four bankruptcies. NBC fired him in 2015.

Foreshadowing our current political culture – and Instagram – Postman made this argument nearly four decades ago: “Americans no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas, they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials.”

Richard Campbell (campber@miamioh.edu) is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami University. He is the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.