Media Matters: The Reading Problem – Part II

“A mind needs books as a sword needs a whetstone, if it is to keep its edge.” --George R.R. Martin

In 2022, a worldwide study by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences reported that the U.S. placed 20th in terms of adults who read at least one book a year. Sadly, we ranked just behind Latvia.

A new study from YouGov reported that 40% of American adults read no books in 2025.

So what does this mean? According to iScience, numerous studies reveal the benefits of reading, including “gains in comprehension skills, vocabulary, logical reasoning, imagination, emotional intelligence, and empathy, to links with academic achievement, financially rewarding employment, career growth, and involvement in civic life….”

I interviewed local educators about the challenges, nuances and possible solutions to the reading problem amid the allure of social media, YouTube and video games.

Erik Jensen, associate professor of history at Miami, reported on a Humanities Center initiative, The Reading Project, a faculty research collaboration “exploring three interrelated questions: What value does reading have? Why do so many students seem to find reading difficult and/or unimportant? And what can we, as university instructors, do about it? We are currently only halfway through this project, and we are … planning on presenting our findings in an informal symposium sometime in April.

“So far, though, I have learned that the picture is a lot more complicated than the media have sometimes presented it. If one counts just the sheer number of words that students read these days (including texts, emails, X or BlueSky posts, newsfeeds, etc.), they are actually reading a LOT more than our generation did when we were in college. They are most often reading very differently, however – in shorter bites, across multiple platforms and shifting between them regularly…. At the same time, it is true that most students engage in deep, immersive reading less than earlier generations of students did. Of course, that statement is true of the entire population today! So, what to do about it? One key takeaway is that I need to meet my students closer to where they are. “I can still assign more reading than they might want, but I can't be completely unrealistic in my expectations. Finally, I will add that there are students who still do read avidly and thoroughly, and they are genuine assets in the classroom.”

Andrew Hebard, associate professor of English at Miami, offered this: “I teach a class, Books You Need to Read, that I just redesigned. I increasingly found that students were having difficulty reading long form prose and (more recently) were using AI to summarize texts rather than reading the texts themselves. The redesign of the course still incorporates some longer novels, but the focus of the course has really shifted from the ‘books’ to the act of reading. The students themselves are often deeply concerned about their own capacities for attention and reading. I had a number of students say that they actually read more in high school than they do at Miami.”

“There are definitely challenges with getting students to read complex books and excerpts,” said Ashley Sammons, an English teacher at Talwanda High School. “Phones, computers, and social media provide instant gratification and books do not.

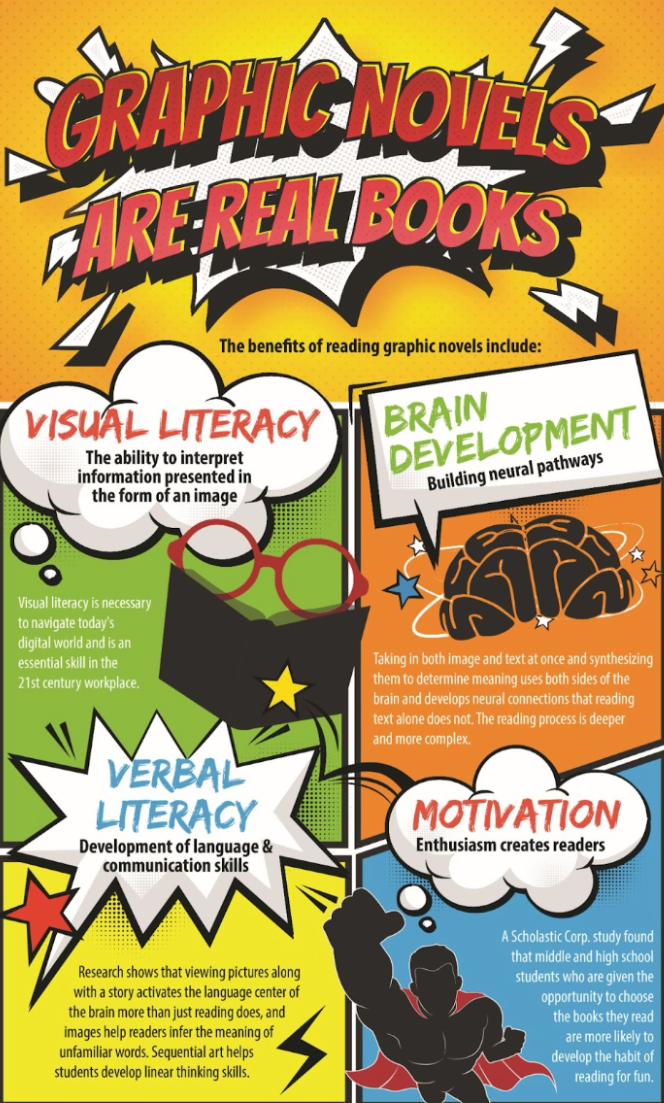

Like Hebard, Sammons has found creative ways to accommodate students in our digital age: “I have definitely changed how I approach teaching books and spend much more time attempting to hook my students with previewing activities, group work … and short pieces they relate to. I am more relaxed with what students can read independently because at the end of the day, I would rather them read something than nothing at all. Graphic novels, books in verse, and mass market books appeal to many students and reading independently should ultimately be something students enjoy.

“I am certainly not claiming to have a magic answer to get students to read instead of spending time on social media and YouTube. Students often tell English teachers they have not finished a book since elementary school, so finding one that is of high interest is often a goal for me in the classroom. We are never 100% successful, but finding a book that makes a student excited about reading is one of the best parts of the job. I think modeling good reading habits at home, setting aside screen-free time each day, or even having family reading time are great suggestions. Books that seem to be popular include “The Hunger Games” series … and “Long Way Down” by Jason Reynolds.”

Marcy Hemmert Hughes and Ann Calderone Bertke, English teachers from my alma mater, Carroll High School in Dayton, shared their combined wisdom: “The challenges are no different than what any English teacher has ever faced. Some students will always be reluctant, especially in a world where the concentration appears to be STEM coursework. There will always be readers and non-readers. The key is not to dumb down the literature, but to relate it to current happenings … and universal truths.

“Teaching whole books has always been our focus, but more important is engaging with the text somehow: acting out scenes from plays, looking at a novel’s structure, and finding imagery throughout. Using audio books, online comic book subscriptions, and graphic novels helps. For example, we just added the graphic novel version of “To Kill a Mockingbird” to our freshman curriculum. This does not mean that we are not teaching whole novels … but literature will live if we use other formats. We have to recognize that we have a lot of students with subscriptions to online comic books series, graphic novels, even nonfiction materials. All of this is reading.”

My daughter, Caitlin Campbell, children’s librarian at Oxford Lane Library, echoes the creative adjustments: “Teens, especially teen boys, are notorious for snubbing pleasure reading. There are certainly outside forces that contribute to this – technology and social pressures, for example – but there are things parents can do to try to prevent this. One of the most impactful things parents can do is model their own love of reading by reading in front of their kids often. This could be something as simple as having 20 minutes of daily (or weekly) family reading time where the whole family gathers to read in the same room.

“One thing I really want to caution parents about is stigmatizing and belittling the formats and genres kids and teens are interested in. I see this happen all the time at the library with comics and graphic novels (‘Put that graphic novel back and pick a real book.’) The fastest way to kill a child’s love of reading is to steer them away from the books that bring them joy.”

Richard Campbell (campber@miamioh.edu) is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami University and board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.