Media Matters: YouTube, the elephant in the room

For those of us who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s, our parents worried about too much TV viewing. That seems like child’s play in comparison to this age of smartphones and on-demand video.

While researching a column on the future of network TV, I got sidetracked by YouTube (or YubeTube as our preschool grandson calls it).

YouTube, 20 years old now, was started by three guys from PayPal in 2005 and sold to Google a year later for $1.65 billion – a bargain since today the streaming giant generates more than $36 billion a year in revenue for Google.

I was doing a phone interview about network TV with Jeff Conroy, a 1994 Miami University graduate and Emmy-winning former executive producer of Discovery’s “Deadliest Catch,” a cable reality show about fishing – and related family drama – now in its 21st season. Conroy, who moved on from “Deadliest Catch,” wasn’t sure about the future of the networks, since he has mostly produced programs for cable and streaming services. But he said that in the end, anyone making TV shows these days has to contend with “the consumer YouTube experience.”

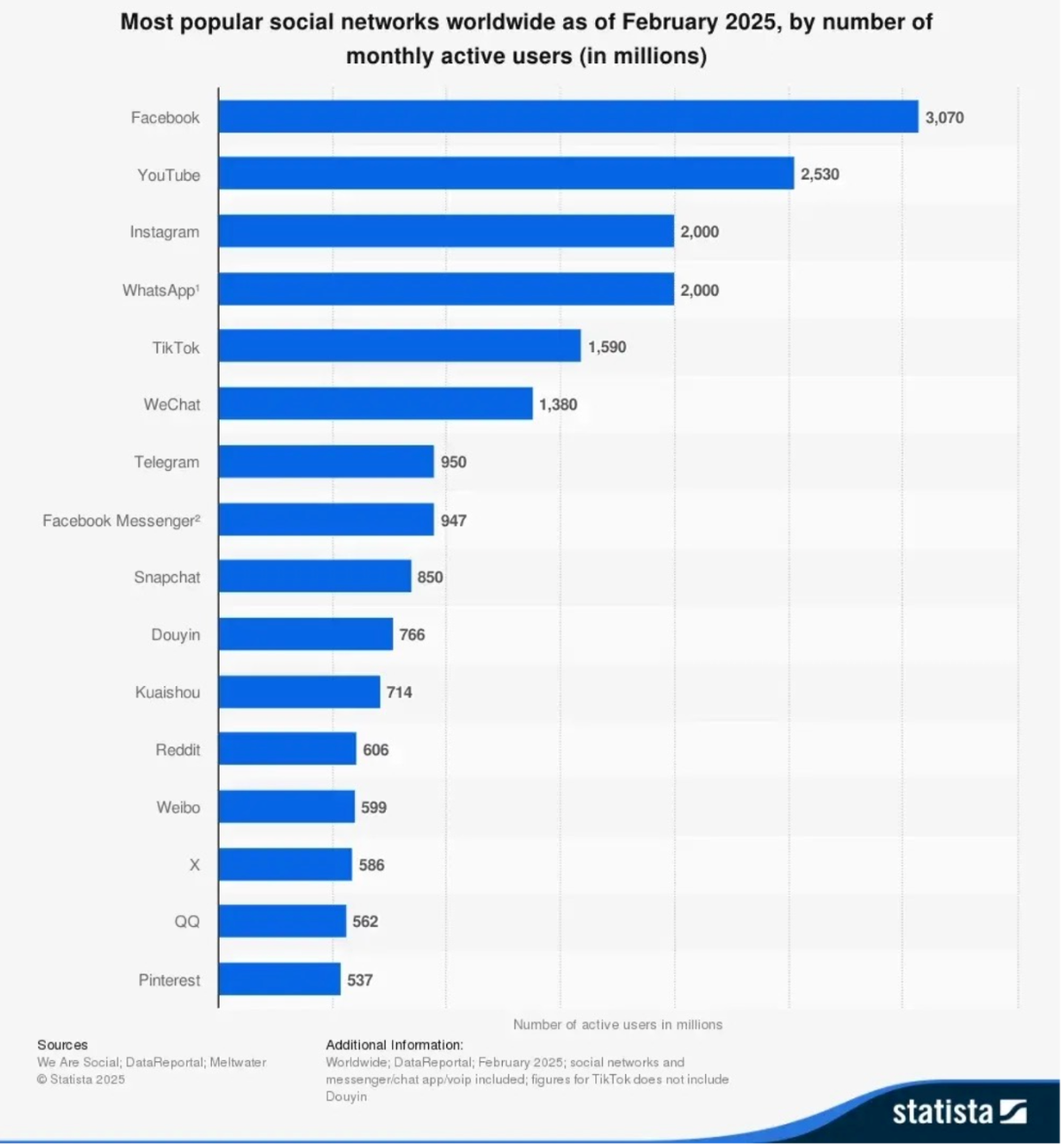

Worldwide, about 500 hours of videos are uploaded every minute on YouTube, which is available in more than 100 countries and in 80 languages. Roughly 2.7 billion people hit YouTube each month, with India, the U.S, and Brazil the three biggest users. More than 60% of the over 250 million U.S. internet users visit YouTube each day.

The biggest hit on YouTube is a program, or channel, called MrBeast, which has 445 million viewers worldwide. I had never heard of it. Jimmy Donaldson, aka MrBeast, apparently earned $700 million last year from ad revenue generated by the program, as described on Wikipedia – “high-paced YouTube videos built around elaborate challenges and grandiose philanthropic efforts, that are noted for their high production values.” In a $100 million deal, he is now producing a reality competition show called “Beast Games” for Amazon Prime.

Moving on, if I want to know how to patch a hole in ceiling drywall, transform a Transformer action figure, or put up an unwieldy artificial Christmas tree, there is someone in the universe who has done it and posted a video.

Do we even need instruction manuals anymore?

If I want to watch an old performance of “The Weight” by The Band and the Staple Singers (highly recommended), I can. If I want to watch recaps from a Reds game (without enduring over two hours and another loss), it’s a click away. After the World Series, I got hooked on old Babe Ruth film clips. For my wife, it’s a fascination with the beauty, athleticism and improvisation of West Coast swing dancing (also highly recommended). For our grandchildren, first it was Miss Rachel when they were younger, then on-demand mermaid and zombie videos. We await the next phase.

For those of us who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s, our parents worried about too much TV viewing. That seems like child’s play in comparison to this age of smartphones and on-demand video. The range of content is significant. There are “Baby Shark” videos for toddlers that have achieved 16 million hits and National Geographic’s YouTube site has 24 million subscribers. YouTube gives viewers what they want, when they want it. Anyone’s current interest or information need is satisfied in an instant. We can also discover new interests and information on YouTube. Who knew I could find a 1930s Babe Ruth film clip instructing young women how to hit and throw?

There are, of course, downsides. If you have YouTube with ads, you can fall down a digital rabbit hole trying to learn the secret to a happier life from a gut doctor or a hair-loss con artist.

More seriously, a recent Australian study from Griffith University noted, “Frequent users of YouTube have higher levels of loneliness, anxiety, and depression.” YouTube may not be the cause of these emotions, but simply serve as an attraction or distraction for people already suffering from loneliness, anxiety, and depression. The researchers found that “the most negatively affected are individuals under 29 years old, or those who regularly watch content about other people’s lives.”

I wrote an earlier column about the correlation between declines in reading and increases in screen time, which include hours devoted daily to short form videos on TikTok and YouTube. One of Google’s own early studies found that “40% of teenagers reported that they believed that their favorite YouTube content creators understood them more than their real life friends.”

Psychiatrist Maurice Preter’s “YouTube and Mental Health: How Video Content Shapes Emotional Well-Being” discusses YouTube’s educational content and its potential for community building and creative expression. On the “darker side,” Preter notes how overreliance on YouTube (along with Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok) encourages “comparison culture” – where watching an influencer's strategically staged lifestyle can lead obsessed viewers to feelings of inadequacies, contributing to “loneliness and detachment from real-life interactions.” Then there’s “screen time overload” that can lead to shorter attention spans in school and sleep deprivation at home.

These two anonymous comments on another social media site, Reddit, do a good job of capturing our complex relationship with YouTube:

“I like watching youtube chefs and funny talking animal videos before bed. Doesn’t make me feel lonely.”

“I really need to cut YouTube out of my life. It’s by far the most toxic way I spend my time (and there’s some stiff competition there considering it's competing with video games and Reddit.)”

Richard Campbell (campber@miamioh.edu) is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami University. He is the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.

Support us here!