Observations: The Nuclear Age

Around 1993, when I published “Life Under a Cloud,” my history of the atomic age, I was marginally hopeful.

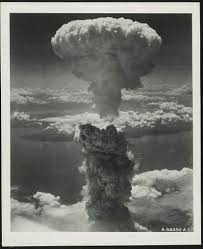

Last month marked the 80th anniversary of the nuclear age.

In August 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on two cities in Japan – Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Those bombs killed tens of thousands of people, injured more, and ensured that the world would never again be the same.

Americans initially hailed the new weapons. After all, they led the Japanese to surrender and brought a cataclysmic global war to an end. But with the publication of novelist John Hershey’s “Hiroshima” in 1946, first in the “New Yorker” magazine and then as a book, they began to contemplate the consequences of this fearsome new weapon. His dispassionate account of the awful destruction was so understated that it was horrifying.

In the years that followed, weapons became even more fearsome. Fission bombs, which relied on splitting the atom, gave way to hydrogen fusion bombs in a process similar to what happens on the surface of the sun. It had the power to wipe out the human race. People talked casually about entire cities, even entire countries, being destroyed. At one point, scientists predicted that a worldwide nuclear war would cause a nuclear winter that would destroy the human race.

Some people joked about what was going on. “Atom Bomb Baby” was a popular song in 1957. Musical humorist Tom Lehrer sang, “so long, mom, I’m off to drop the bomb, so don’t wait up for me.”

But fears persisted. An arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union grew more heated every year, and the only thing that kept us alive was the perverse policy of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) – the awareness that if our enemy dropped a bomb on us, we would retaliate in kind, and, in the end, everything would be destroyed.

Eventually sanity prevailed. The Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) in 1963 was the first step, followed by the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT). Later, the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) ensued, followed by the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

The doomsday clock on the cover of the “Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists,” the major publication about nuclear weaponry, gradually began to add minutes as danger receded.

Around 1993, when I published “Life Under a Cloud,” my history of the atomic age, I was marginally hopeful.

But now I am more worried than before. More countries are gaining atomic capability. The treaty President Barack Obama negotiated to limit Iran’s nuclear development was cancelled by President Donald Trump. A recent article in the “New Yorker” suggested that people don’t seem to care about the atomic threat anymore, even though it is more dangerous than before, as Trump and Russian leader Vladimir Putin casually contemplate using these weapons of destruction. Virtually all of the treaties of the past are now gone, with the last one set to expire soon. The doomsday clock now stands at 89 seconds before midnight.

It is frightening to feel that we are on the brink of something truly scary. Years ago, during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1963, we felt that we were closer than ever before to nuclear war. We survived that debacle then. Today, I am sorry to say, the threat seems even closer.

As I contemplate our nuclear future, I am more worried than ever before. And I can only hope that we will do what is necessary to survive.

Allan Winkler is a University Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus at Miami University, where he taught for three decades. He serves on the Board of Directors for the Oxford Free Press.