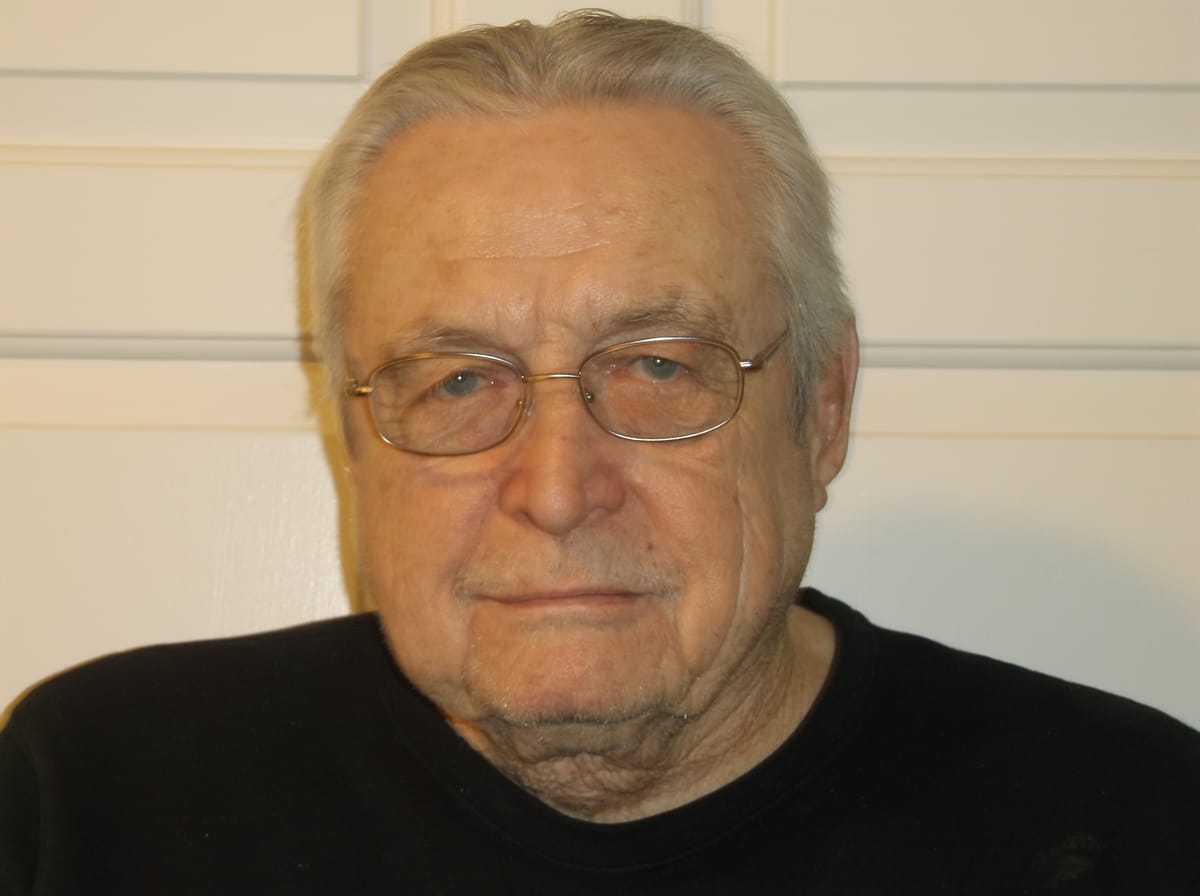

Veterans Among Us: Doug Jordan

"Once, I sat down with Jordan in his Oxford living room and he shared that his family had relocated from Detroit, Michigan to Liberty, Indiana early in his childhood. He grew up next to a Veterans of Foreign War (VFW) post that was across the street from his home."

I met Doug Jordan a few years ago at a social gathering. He didn’t have much to say on our first meeting, but his conversation came alive when he first saw me again – with his Vietnam Veteran hat on.

Over our next several meetings, our conversations drifted to Vietnam and the impact the war had on our lives while serving in the US Army.

Once, I sat down with Jordan in his Oxford living room and he shared that his family had relocated from Detroit, Michigan to Liberty, Indiana early in his childhood. He grew up next to a Veterans of Foreign War (VFW) post that was across the street from his home.

Jordan shared that he had uncles that served in WWII and that his brother served in the Marines in the mid 60’s. He also shared that none of these men ever talked about their time in the service.

Jordan was drafted after high school (Liberty, class of 1966) into the Army and he was off to basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina in April 1968. After this, he was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia for advanced infantry training (AIT).

He traveled to Vietnam after AIT, but was delayed when he was part of an entire Army Division that was diverted to Germany to counter some Russian border flare ups. This temporary duty lasted about three months before he returned to Fort Reilly, Kansas. He immediately got orders to Vietnam in April, 1969.

At Fort Benning, a number of Army classroom tests identified his skills in radio repair. He became part of the Army Signal Corp as a RTO (radio telephone operator). RTO became his Army military occupation specialty, or MOS.

Jordan shared his emotions as he was winging across the world to Vietnam.

“My biggest fear was would I be able to pull the trigger if I had to,” he said. My seat mate was a 19-year-old helicopter pilot.”

In Bien Hoa, the Army’s replacement center, Jordan was assigned to the 4th Infantry Division that was operating in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. He was soon on a plane to Pleiku, Vietnam and the division’s headquarters at Camp Enari. This camp was named after 1st Lieutenant Mark Enari, who was killed in December 1966. A few days after his arrival at Enari, he was assigned to the division’s D Company, 1st Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment as an RTO for the company’s commanding officer.

“One week after this assignment, we had to fly into our area of operations, to the rescue of a sister company that had gotten ambushed,” Jordan said. “After this, I was always operating out of our Division’s fire bases. I always had to carry a double load (of) my regular stuff along with my radio while on patrol."

Jordan operated out of these fire bases, which were distant camps away from the Enari base camp for nine months. Fire bases were used as large camps, primarily for patrolling. Other than walking to and from them, they were only accessible by helicopter. They were protected by those who lived on them.

“One irony of fire base duty was that my seat mate on my flight to Vietnam, the 19-year-old warrant officer was often flying in to support my unit,” Jordan said. “His radio call sign was Black Jack 22.”

Jordan estimated that he flew in thirty combat assaults in Vietnam from these firebases. This meant loading into a helicopter, flying to an unknown destination, being dropped and then patrolling often for long stretches of time.

“I learned to overcome my fear because I had to,” Jordan added. “We were chasing North Vietnamese regulars (also known as the People’s Army of Vietnam) when, in fact, they were chasing us.”

“I eventually got assigned to the base camp toward the end of my tour,” Jordan said. “By this time, I was a Sergeant, E5, running communications for the base camp. I had a lot of authority.”

Jordan returned home to the United States in March 1970.

Jordan discussed some positives from his service.

“My time in service taught me self-discipline,” he said. “I had little of this before I served (and) I learned when something needs to be done, I just do it.”

After these discussions, Doug showed me his office, including multiple mementos of his service hanging on the wall.

His Purple Heart award was prominent, but he said he was most proud of a simple plaque presented to him by his unit in Vietnam that thanked him for everything he had done to support their mission.

When asked, all things considered, if he would consider doing what he did in Vietnam over again Jordan answered without hesitation: “in a heartbeat.”

Some readers would be surprised at this reaction, yet millions of other veterans might say the same thing.

Consider what Author Michael Clodfelter said in “Mad Moments and Vietnam Months:”

“Men would give their loyalty and respect not to the glory hounds but to the strong, steady, solid men who shrugged off glory’s temptations, held up their end in a fire fight, carried their share of the load on a march, served their time as point man at the head of a column, or resisted the temptation of pretended illness to desert their comrades in the bush. These were the kinds of men you respected and were determined to become, even at the risk of death.”

Jordan and others who have been in armed conflict have done what their county ask them to do in spite of the consequences. Given this choice, it’s up to everyone to decide what we owe them.

Lee Fisher is a Miami graduate, resident of Oxford, Ohio and a Vietnam War Veteran.